Astronomers Reassured by Record-breaking Star Formation in Huge Galaxy Cluster

August 12, 2012

Until now, evidence for what astronomers suspect happens at the cores of the largest galaxy clusters has been uncomfortably scarce. Theory predicts that cooling flows of gas should sink toward the cluster’s center, sparking extreme star formation there, but so far – nada, zilch, not-so-much.

The situation changed dramatically when a large international team of over 80 astronomers, led by Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Hubble Fellow Michael McDonald, studied a recently discovered (yet among the largest-known) galaxy cluster. The team found evidence for extreme star formation, or a starburst, significantly more extensive than any seen before in the core of a giant galaxy cluster. "It is indeed reassuring to see this process in action," says McDonald. "Further study of this system may shed some light on why other clusters aren’t forming stars at these high rates, as they should be."

The result, published in the August 16th issue of the journal Nature, began developing in 2010 when data from the South Pole Telescope (SPT) allowed astronomers to identify the huge cluster of galaxies some 5.7 billion light-years distant. Designated SPT-CLJ2344-4243, it is among the largest galaxy clusters in the universe.

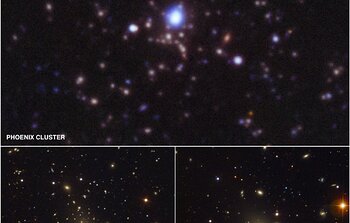

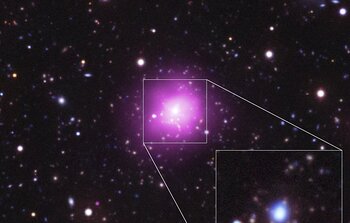

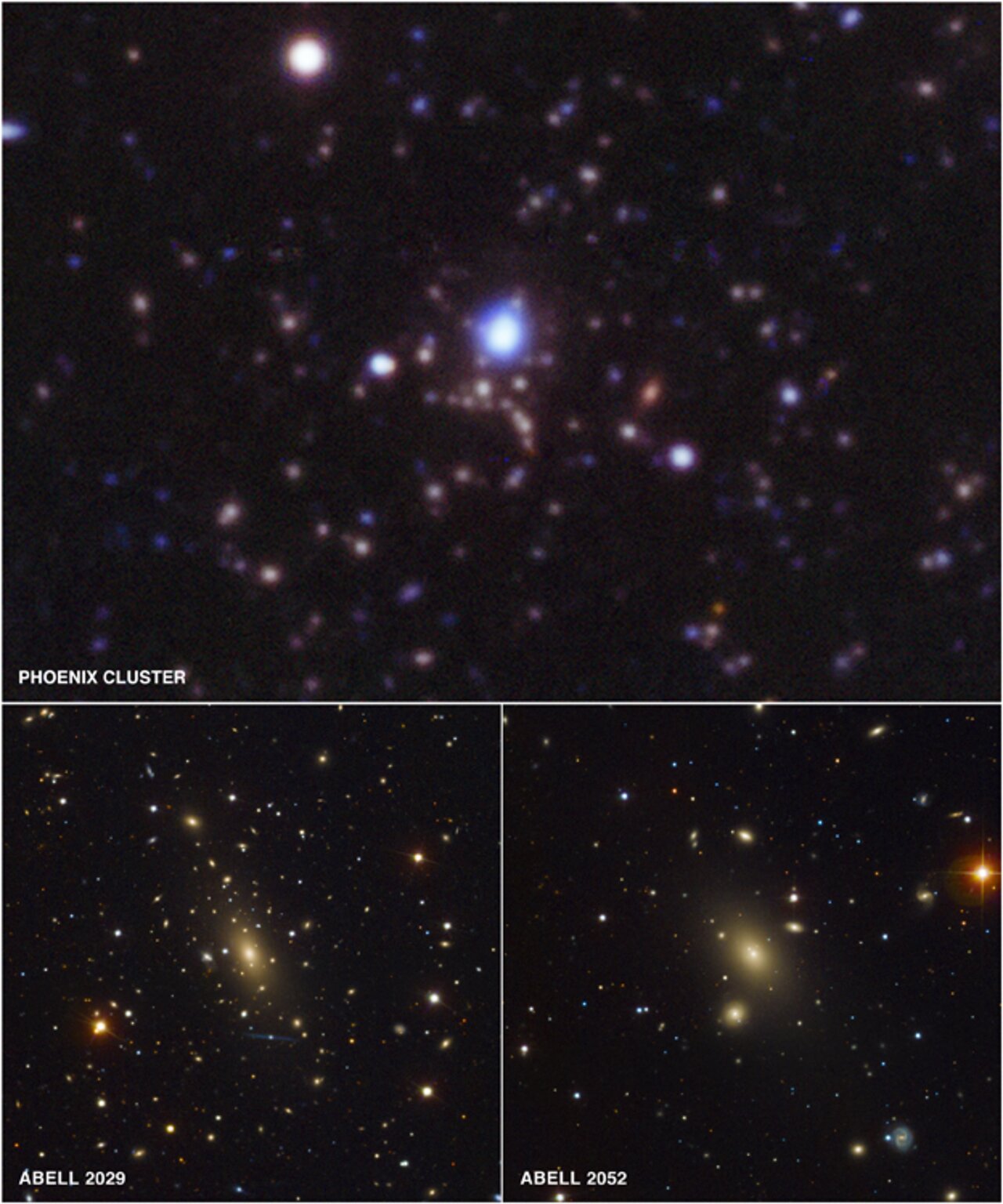

"Our first observations of this cluster with the Gemini South telescope in Chile really helped to ignite this work," says McDonald. "They were the first hints that the central galaxy in this cluster was such a beast!" The paper's second author, Matthew Bayliss of Harvard University, adds, "When I first saw the Gemini spectrum, I thought we must have mixed up the spectra, it just looked so bizarre compared to anything else of its kind." Bayliss and Harvard graduate student Jonathan Ruel used the Gemini data to determine the cluster's distance; they also corroborated its huge mass with estimates from X-ray data obtained with the Chandra X-ray Observatory. Additional survey data from the National Optical Astronomy Observatory's (NOAO) Blanco Telescope in Chile augmented the early characterization of this cluster. A Blanco image of the cluster (Figure 1, top) is available as part of this press release.

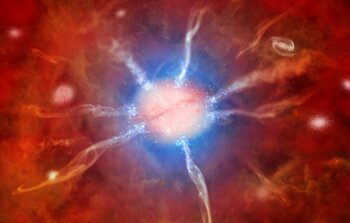

With this result, astronomers now believe they have finally seen, at least in this one large cluster of galaxies, what they expected to find all along - a massive burst of star formation, presumably fueled by an extensive flow of cooling gas streaming inward toward the cluster's central core galaxy. The sinking gas is likely sparking star formation and a lively, dynamic environment - somewhat like a cold front triggering thunderstorms on a hot summer's day. This is in rich contrast to most other large galaxy clusters where central galaxies appear to have stopped forming new stars billions of years ago – an uncomfortable discrepancy known as the "cooling-flow problem."

According to theory, the hot plasma that fills the spaces between galaxy cluster members should glow in X-rays as it cools, in much the same way that hot coals glow red. As the galaxy cluster forms, this plasma initially heats up due to the gravitational energy released from the infall of smaller galaxies. As the gas cools, it should condense and sink inward (known as a cooling flow). In the cluster's center, this cooling flow can lead to very dense cores of gas, termed "cool cores," which should fuel bursts of star formation in all clusters that go through this process. Most of these predictions had been confirmed with observations—the X-ray glow, the lower temperatures at the cluster centers— but starbursts accompanying this cooling remain rare.

SPT-CLJ2344-4243, nicknamed the "Phoenix Cluster, lies in the direction of the southern constellation Phoenix, which McDonald suggests is fitting. "The mythology of the Phoenix – a bird rising from the dead – is a great way to describe this revived object," says McDonald. "While galaxies at the center of most clusters may have been dormant for billions of years, the central galaxy in this cluster seems to have come back to life with a new burst of star formation."

The team combined multiple ground- and space-based observations including data from the Gemini South 8-meter and the NOAO Blanco 4-meter telescopes, both in Chile and funded with support by the U.S. National Science Foundation (as is the South Pole Telescope which made the initial discovery of this galaxy cluster in 2010). Observations critical to this research also included the Chandra X-ray Observatory, NASA's WISE and GALEX observatories, and the European Space Agency's Herschel Observatory.

Banner images courtesy of the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

Links

Contacts

Peter Michaud

pmichaud@gemini.edu

(808) 974-2515

808-936-6648

Gemini Observatory

Hilo

Hawai‘i

Antonieta Garcia

agarcia@gemini.edu

56-51-205628

Gemini Observatory

La Serena

Chile

Michael A. McDonald

mcdonald@space.mit.edu

617-324-1075

Hubble Fellow MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research

Matthew Bayliss

mbayliss@cfa.harvard.edu

617-496-0532

336-317-8981

Postdoctoral Fellow Harvard University Dept. of Physics The Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics